How the Halo Effect Distorts Investment Decisions

The halo effect causes investors to overestimate people, companies, and assets based on a single positive trait — often leading to poor financial decisions.

The halo effect is one of the most underestimated cognitive biases in investing — and paradoxically, it tends to affect intelligent and experienced people more than beginners.

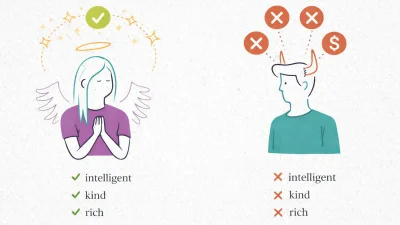

When we like one trait in a person, company, or asset, the brain subconsciously fills in the rest. Smart becomes reliable. Successful becomes universally competent. Confident becomes correct.

What is the halo effect?

The halo effect occurs when a single positive characteristic influences our overall judgment, even in areas where no evidence exists.

Instead of evaluating each attribute independently, the brain applies a global “positive score.” It’s efficient. It’s fast. And in finance, it’s dangerous.

Why smart people fall for it

The halo effect is especially powerful among those who:

- Excel in one professional domain

- Have already achieved measurable success

- Trust their analytical abilities and intuition

Success creates confidence. Confidence creates mental shortcuts. Over time, this leads to a false sense of universality — the belief that competence transfers automatically across domains.

How the halo effect shows up in investing

In financial markets, the halo effect often appears in subtle but costly ways:

- “He built a successful business — his investment advice must be solid.”

- “The company has a great product — the stock is obviously a buy.”

- “She sounds confident — she must be right.”

In each case, judgment is outsourced from analysis to perception.

The brain’s energy-saving trick

The human brain is designed to conserve energy. Evaluating every variable independently is cognitively expensive.

So instead, the mind assigns a general label — good or bad — and stops digging. This shortcut works in everyday life. In investing, it often leads to mispricing risk, overconfidence, and capital loss.

A hard truth investors avoid

Success in one area guarantees nothing in another.

A brilliant entrepreneur can be a poor portfolio manager. A charismatic CEO can run an overvalued company. A strong past performance does not ensure future returns.

The next level of thinking

Skilled investors train themselves to separate:

- Personality from performance

- Charisma from competence

- Past success from future returns

Every decision, asset, and individual must be evaluated on its own metrics — not on borrowed credibility.

A simple mental checkpoint

If you catch yourself thinking:

“Well, he’s smart / successful / famous…”

Pause.

That’s usually the moment analysis stops and belief takes over.

And belief, while comforting, is a poor strategy for capital allocation.

Emily Turner

Emily Turner