London Masks a Deep Economic Divide Inside the UK

London continues to outperform economically, but the UK’s growing dependence on its capital is exposing deep regional, housing and productivity imbalances.

London remains one of the world’s most powerful financial centres. Capital flows in, global banks stay anchored, and wealth continues to accumulate. On the surface, the city looks like a success story.

But from a macro perspective, that strength is increasingly masking a deeper problem. The UK economy has become structurally dependent on London — and the gap between the capital and the rest of the country continues to widen.

A Capital That Skews the Numbers

London’s economy alone is estimated at roughly $500 billion, placing it on par with mid-sized European countries. If the city were measured independently, it would rank among the top 30 economies globally.

Remove London from the equation, however, and the picture changes quickly. UK GDP per capita would fall by around 14%, leaving national income levels below those of the poorest U.S. states.

In effect, the capital now lifts the national average almost single-handedly — while large parts of the country lag well behind it.

Two Economies, One Currency

From a market standpoint, this matters. Currency strength, fiscal sustainability and productivity trends are ultimately national metrics, even when growth is not evenly distributed.

The UK increasingly resembles a “two-speed” economy. London and the South East operate like a high-income European hub. Many regions elsewhere face stagnant wages, weaker investment and slower productivity growth.

No region north of London currently exceeds the national average in GDP per capita — an average that is itself inflated by the capital.

Housing Pressure as a Macro Constraint

The housing market has become a binding constraint on growth, particularly in London.

Across England, average house prices now exceed eight times annual earnings. In London, that figure rises beyond twelve. For younger households, entry into home ownership has become increasingly unrealistic.

Policy decisions made decades ago still shape today’s market. The large-scale sale of social housing in the 1980s boosted ownership in the short term, but replacement construction failed to keep pace.

As a result, London’s social housing stock has fallen by more than 60% since 1980. Many of those properties are now held by private landlords and rented back at market rates.

Foreign demand has added another layer of pressure. Roughly a quarter of London home purchases in early 2024 were made by overseas buyers — often treating property as a store of value rather than a place to live.

Infrastructure and Productivity Gaps

Investment patterns reinforce the imbalance. Public spending on transport per person in London remains several times higher than in many northern regions. Poor connectivity limits labour mobility and reduces the effective size of regional cities.

For markets, this shows up in productivity data. Unlike most advanced economies, UK city size does not strongly correlate with productivity — a clear sign of infrastructure constraints.

The Long Shadow of Deindustrialisation

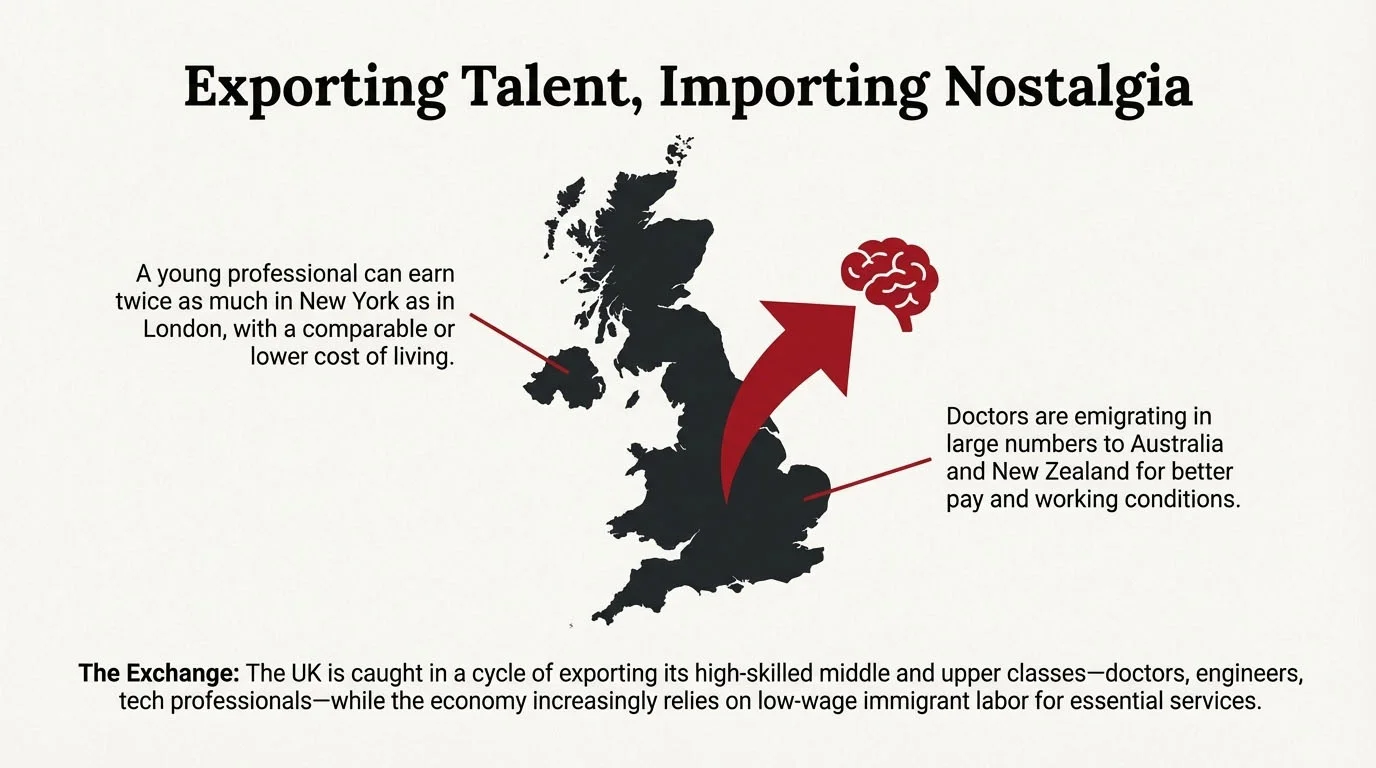

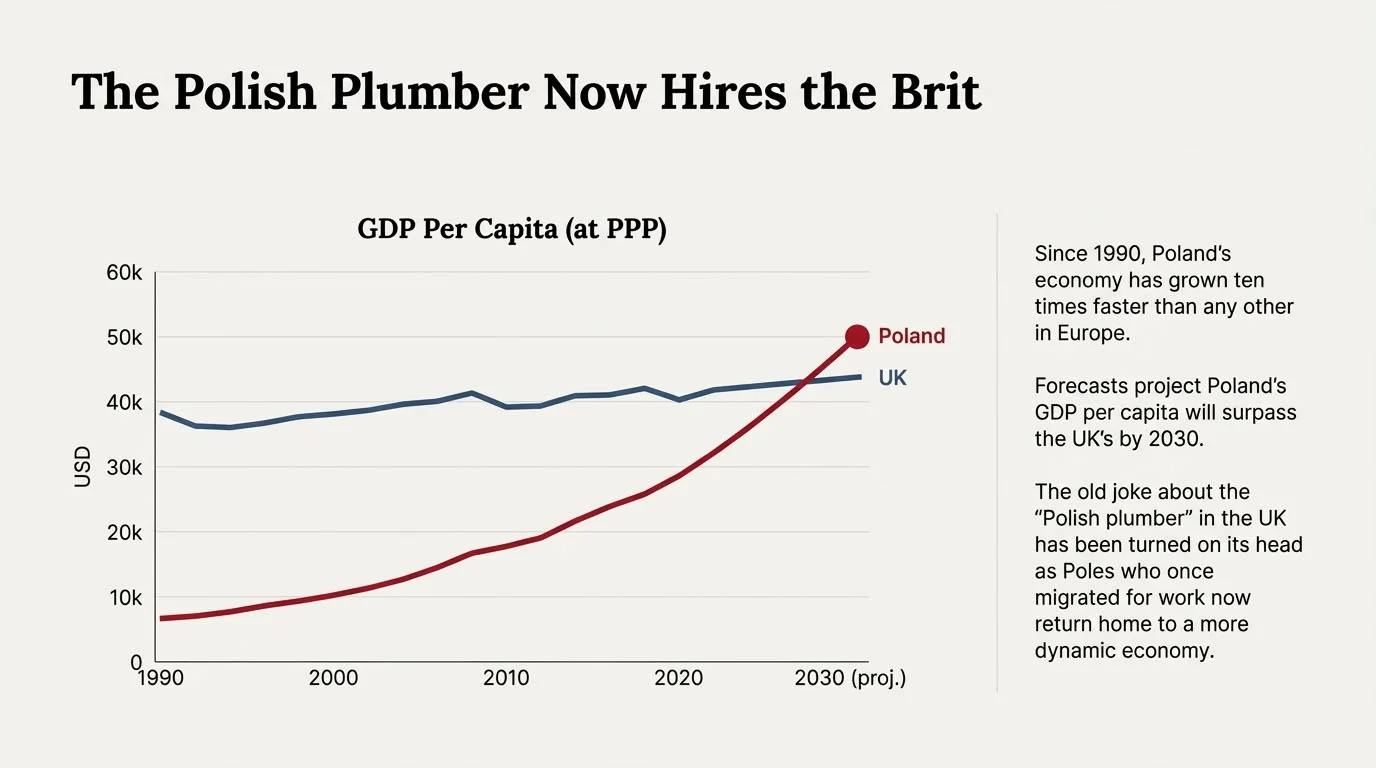

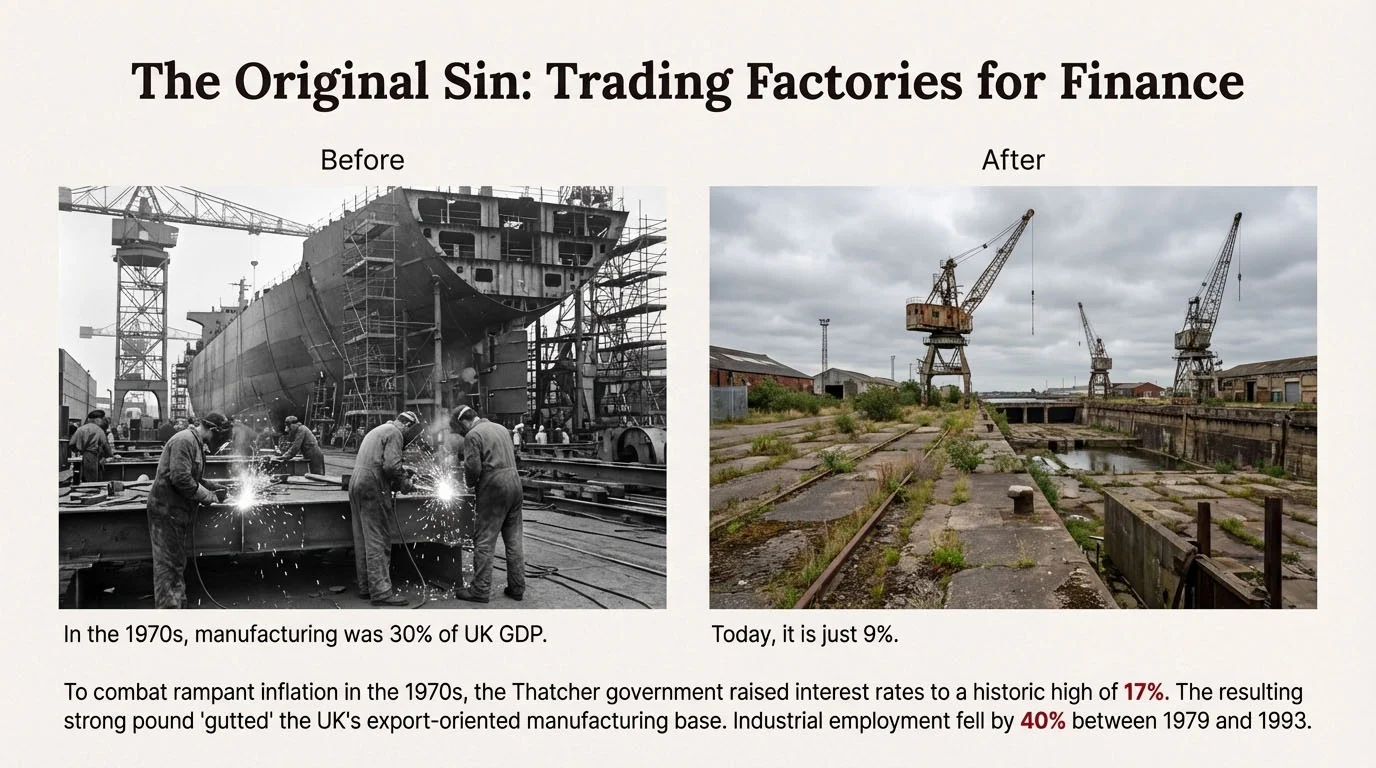

The UK’s reliance on London also reflects long-term structural choices.

Manufacturing once formed the backbone of regional economies. Today, it accounts for less than 10% of GDP. The shift toward finance boosted headline growth but concentrated activity geographically.

Financial services generate high value but relatively limited spillover employment. Regions that lost industrial capacity were left without comparable replacements.

Recent Shocks Have Exposed Fragility

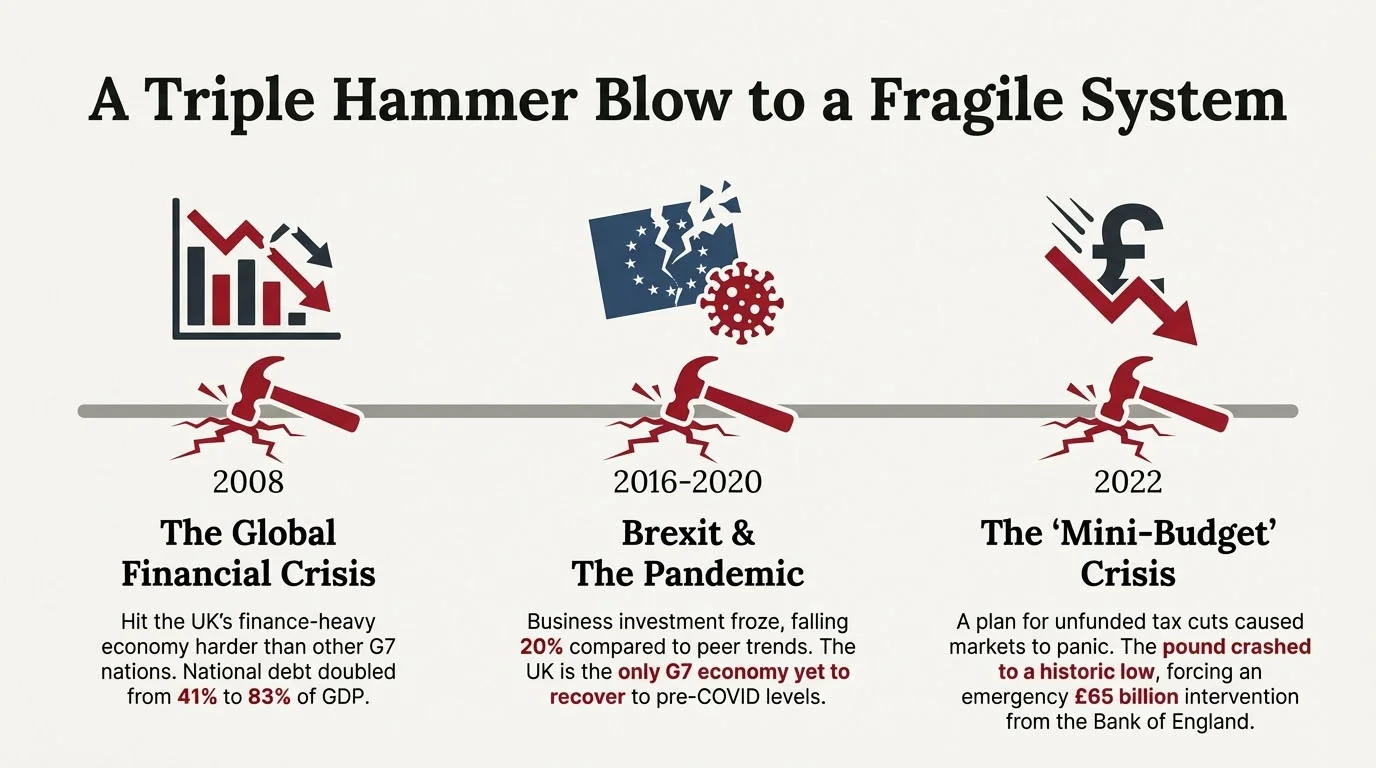

This model proved vulnerable when tested. The 2008 financial crisis hit the UK particularly hard. Brexit then froze business investment, followed by the pandemic. More recently, the 2022 fiscal shock triggered market volatility that forced emergency intervention from the Bank of England.

Each episode reinforced the same message: concentration increases risk.

What Markets Are Watching Now

London’s dominance is not in question. It remains a global hub for capital, talent and financial infrastructure.

The issue is whether the rest of the UK can regain momentum. Without broader-based investment in housing, transport and regional productivity, the gap is likely to persist — limiting national growth potential.

For investors and policymakers alike, the challenge is clear. A capital-led recovery can only go so far. Beyond that point, imbalances begin to weigh on the entire economy.

Amelia Hayes

Amelia Hayes