China’s Rising Debt and the Risk of a Financial Shock From the East

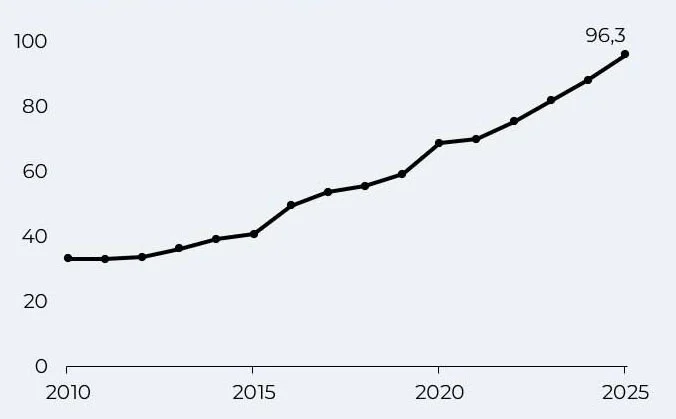

China’s government debt has climbed sharply over the past decade. IMF data and hidden local liabilities suggest the real burden may already rival the U.S.

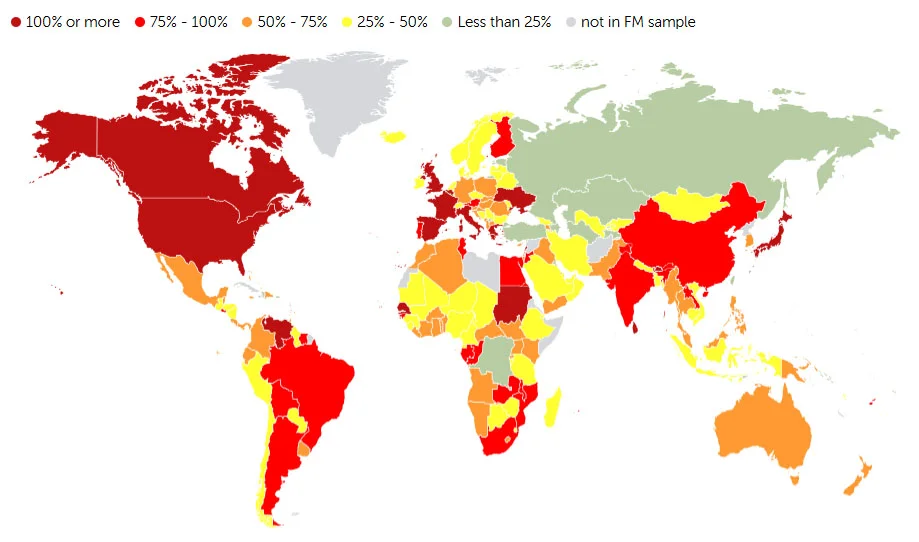

From an editorial perspective, the significance lies in the shift of focus. For years, global markets have debated the sustainability of government debt in the United States, Japan, France, and Italy. Increasingly, however, China is emerging as a comparable source of long-term fiscal risk.

According to data from the International Monetary Fund, China’s gross government debt has risen from around 41% of GDP in 2015 to roughly 96% in 2025. The figures are based on the IMF’s World Economic Outlook database and can be reviewed directly via the IMF data mapper.

Why China’s Debt Has Grown So Quickly

The surge reflects several overlapping pressures. Large-scale fiscal spending during the pandemic played a role, but more persistent drivers remain in place: intensifying technological competition with the United States, prolonged trade tensions, and — most critically — the collapse of China’s property sector.

Despite the end of pandemic-era restrictions, Beijing continues to run a sizable fiscal deficit. In 2025, the budget shortfall is estimated at around 8.6% of GDP, with little indication of near-term consolidation. In practice, this means debt dynamics are still moving in the wrong direction.

The Hidden Layer: Local Government Financing Vehicles

Official debt figures understate the scale of China’s obligations. For years, local governments relied on so-called Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs) — quasi-corporate entities used to borrow off balance sheet. These entities issued bonds and financed infrastructure projects, with repayment often tied to land sales.

That model has broken down. The property downturn has sharply reduced land-sale revenues, leaving LGFVs with large liabilities and limited cash flow. To prevent defaults and contain stress in smaller regional banks, the central government has increasingly stepped in to assume or backstop these debts.

When these hidden obligations are included — a task complicated by their opaque structure — estimates suggest China’s effective government debt burden already exceeds 125% of GDP.

Why This Matters for Global Investors

At that level, China’s debt load is comparable in scale to that of the United States. The difference is not the size alone, but the structure: slower potential growth, a strained property sector, and limited transparency around local finances.

For long-term investors, this shifts the risk calculus. The probability of a debt-related shock in China is no longer negligible — and may be closer to that of advanced economies than many assume. A future “black swan” from the East cannot be ruled out, particularly if growth disappoints or confidence in local government balance sheets deteriorates.

Debt, as historical cycles often show, rarely becomes a problem overnight. But when it does, markets tend to reprice risk abruptly.

Olivia Carter

Olivia Carter